Robert Beachy, A Nazi Dilemma: Homosexuality and the German Männerbund

In February 1937 Heinrich Himmler delivered a notorious speech to his SS leadership about the threat of homosexuality. Himmler cited familiar homophobic slanders but also made a fascinating argument that the Third Reich was particularly vulnerable, due to the homosocial character of the Nazi party and its organizations. Invoking Hans Blüher by name, Himmler claimed that the broad reception and popularization of the homoerotic Männerbund – a concept Himmler had encountered in Blüher’s writings in 1922 – had found fertile ground in the Nazi movement. With remarkable bluntness, Himmler stated “we needn’t be surprised that we have gone down the road towards homosexuality.”

Himmler’s frank admission that male same-sex desire was a Nazi problem and not an external threat that could be blamed on others is somewhat startling. In this short paper I want to consider the pervasive influence of Männerbund masculinity, which was often explicitly homoerotic, by considering the popular literary culture of the 1920s and early 1930s. This includes works of right-wing figures such as Hanns Heinz Ewers, Ernst von Salomon, or Carl Heinrich Lampel, as well as others on the Left. I also want to contrast this with the biographies of individual “gay” Nazis, whose demise are documented with Berlin Gestapo and Staatsanwaltschaft files. These figures illustrate well the way individual activists were able to reconcile their homosexuality with their commitments to Nazism. (They also seem to justify Himmler’s apparent anxiety.)

Camille Fauroux, Shared Intimacies: a lesbian relationship in a foreign worker’s camp in Berlin, 1943

In 1943, two French women working in Berlin were accused of having had a sexual encounter in the camp where they were living. This paper seeks to explore three historical questions raised by a single judicial record. First, to what extent did the specific setting of the camp allow for the production of queer spaces? Western women workers in Nazi Germany were usually hosted in single sex camps. In this particular case, the camp seems to have enabled the relationship by opening a space for close encounters between women, as well as temporarily separating the heterosexual couple one of these women was part of. At the same time, the collective housing in shared bedrooms also rendered (homo) sexuality highly visible and thus subject to repression and control. Second, I would like to explore what this single case could teach us about the way we should think about NS-state repression of female homosexuality. Indeed these women were not prosecuted for homosexuality per se, but the people in charge of the investigation clearly pressured them to cease their relationship. Third, how much does our collective desire for this kind of sources account for the possibility of its discovery? By telling the ‘archive story’ (Antoinette Burton) behind this document, I would like to explore what it means for a queer history to understand archives as unstable products of our present rather than as mere traces of the past.

Dorota Głowacka, (Re)framing gender: Representations of female bodies in Holocaust photographs

In her seminal book on photography (1973), Susan Sontag described the act of photographing the Holocaust as “a semblance of rape,” perpetrated by the “predatory, phallic lens of the camera”. Sontag’s provocative metaphor was a succinct commentary on the appropriative but also sexualised framework within which images of victims’ bodies had been produced, and then interpreted and recycled in the visual archive of the Holocaust. Dominant conceptions of gender and sexuality structured the way female bodies were captured in Holocaust photographs. They have also shaped how these images have been conceptualized in Holocaust scholarship and perceived in practices of memorialization. Images of female bodies in Holocaust photographs are refracted through tropes that reflect normative views of women as vulnerable and passive, thus erasing their social, political and sexual agency. The reliance on traditional conceptions of femininity to convey meaning most likely accounts for why certain photographs of women have become iconic and have been replicated in memorial publications and in places of remembrance. Drawing on existing scholarship on Holocaust photography (Struk, Hirsch, Zelizer, Didi-Huberman, and others) and on research in the visual collections of the USHMM and Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, I will focus on selected Holocaust photographs and discuss gendered tropes that frame (and often “crop”) representations of female bodies within familiar terms of reference. My inventory of images and tropes will include:

1. The image of a naked female corpse in a still from Henryk Makarewicz’s documentary film of the liberation of Auschwitz, as it has been contextualized within the aesthetic of the female nude.

2. The cropped and retouched Sonderkommando photograph of naked women running to the gas chamber in Auschwitz-Birkenau and the topos of female nudity as the paramount expression of “Eros/Thanatos.”

3. Atrocity photographs from the Lvov pogrom of violated female bodies, frozen in the postures of horror, as the eroticized emblem of “incomprehensible” barbarity and depredation, in juxtaposition to the images of maternal suffering (the Ivanogrod photograph and “the Holocaust Pietà”).

4. Variations on the image of women peeling potatoes (from the ghettoes, scenes of liberation and DP camps) as the trope par excellence of domesticity and nurture amidst horror and devastation.

Katya Gusarov, Sex as life saving means: Survival strategies of Jewish women in the Nazi occupied East

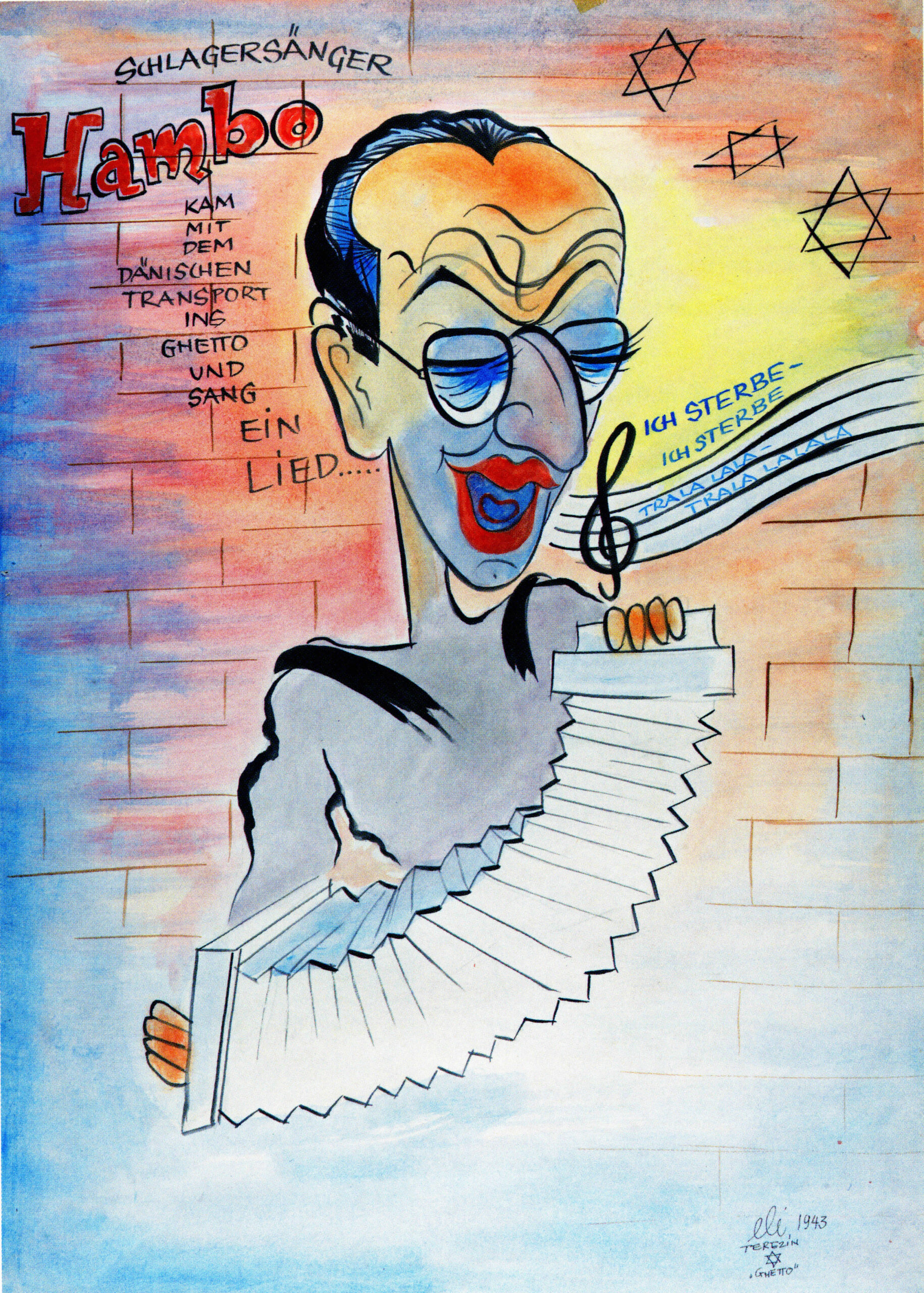

Anna Hájková, Writing a queer history of the Holocaust

Why were certain stories connected to sexuality of the Holocaust victims, such as people who engaged in same sex conduct, never told? Recent scholarship has critiqued the assumption that sexual violence during the Holocaust were deeply traumatizing for the victims and hence are too painful to recount. Sexuality plays a central role in our imagining of genocidal horrors and sexual violence is often used as a pornographic framing mechanism to imagine Holocaust horrors.

My work explores the intersection of sexuality and violence in the Holocaust, and the erasure of certain sexualities from what has become the Holocaust canon. I examine the narrative erasure of lesbians and gays who were deported as Jews, homophobia of the victim society, and sex barter. In examining cases of what I term “transgressive sexuality,” I contribute to our understanding of gender and sexual violence, consent, normative behavior during the Holocaust, and the politics of Holocaust archives.

Dan Healey, Stalin’s Gulag and Popular Homophobia: Structures, stigma, and the Soviet penal queer

The Soviet Gulag of the Stalin era (1930-1953) forged a very visible and unusual set of sexual cultures. Nevertheless, the Gulag’s sexual cultures had a widespread, but still little-studied, impact on late-Soviet sexuality. This paper draws upon a chapter on Gulag sexualities from my forthcoming book, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (Bloomsbury, 2017), to examine the shifting meanings of same-sex sexual activity in the Stalinist camps. The Gulag multiplied the sites of same-sex confinement on an industrial scale across Eurasia, generating more visible and disturbing homosexual relations (coerced & consensual) than Russian and Soviet society had previously been familiar with. It is possible to sketch some of the characteristics of same-sex relations in the Gulag from official archives and memoir sources. In 1950s Gulag experts and officials began to articulate an explicitly homophobic discourse of pathology and criminality, a discourse abundantly evident in their official archives. Their incitement to discourse had impacts on prisoners and Gulag’s political returnees, both groups developing in their own languages discourses of sharp hostility to the queer Other produced by the camps. In the experience of millions of Soviet lives, both those of prisoners and jailers, the penal system of Joseph Stalin and its offspring incubated modern homophobic attitudes even as reformers sought to suppress queer visibility in everyday life. The impact of these attitudes is still felt today.

Gina Herrmann, Sexual violence against Spanish women political prisoners under the Franco regime

During Spain’s Civil War (1936-1939) and well into the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939-1975) Spanish Anti-Fascist women were cast as political, cultural, and gender enemies of the Catholic-Military state. Communist, Socialist, and Anarchist women captured by the regime’s police were systematically interrogated in detention centers across the country. Interrogations entailed sexual violence as a weapon of the Nationalist ‘dirty war’ against the Left. While Spain has experienced an explosion in memory studies focused on myriad aspects of the Francoist terror, in particular, the extrajudicial assassinations of the ideological opposition, Spain does not boast an autochthonous historical or cultural approach to the analysis of the accounts women survivors of the dictatorship have left through orally-inflected memoirs and testimonies. This void means that historians, literary critics and sociologists studying the period in Spain have participated in the ‘globalization of Holocaust discourse’ in which the Shoah becomes a linking metaphor. Spain’s own tragedy finds expression by borrowing from concepts associated with the Holocaust, as well as from the torture of leftist militants during the Dirty Wars in Latin America.

I look at the voicing and interpretation of the testimonial accounts of women who experienced sexual violence under interrogation in 1940s and 50s Spain through the lens of sexualized torture in Latin America and gender torments during the Holocaust. What avenues of expression and modes of articulation have been available to these women emerge from the human rights, antiwar and feminist movements of the 1970s, themselves formations that framed the exposure of crimes against women in the Southern Cone. Unlike the vast testimonial record about sexual torture from Latin America, one that describes rape in detail, Spanish women of the Franco era have more in common in their memorial production with women who suffered sexual violence during World War II: a reticence to describe the corporeal mechanics of abuse and violation.

The second part of this paper makes an incursion into the theory of women’s oral history by asking ‘what kind of artefact is the testimony of sexualized political torture? I look at artist Nancy Spero’s 1976 artwork Torture of Women based on the 1975 Amnesty International Report on Torture. Spero’s graphic manipulation of that report makes visible the halting and silence-marked narrative strategies employed by survivors of sexual torture. Spero’s work eschews the realist depiction of sexually sadistic torture while exteriorizing the damage to the spoken expression of women survivors. I compare images and text from the Spero piece to published oral history accounts of Spanish Republican women.

Ulrike Janz, “Lesbian” as a marker in the Nazi concentration camps

Since the end of the 1980s (and for about 10 years), I researched in a non-university activist lesbian feminist context on what has been told – mostly by Holocaust survivors – about „lesbians,” lesbian behaviour, sexuality, love and friendship between women in Nazi concentration camps. I learned a lot about women and girls in the camps as mostly victims, sometimes perpetrators and more often “Mittäterinnen” (Thürmer-Rohr) in a totalitarian context – not that different from how many (lesbian) feminists around that time discussed women in patriarchy in general. I learned even more about “lesbian” in the camps as a marker, stigma rather than about “real” lesbians/women loving women. My presentation will give a conclusive recollection of my research and a brief overview of the current research.

Elissa Mailänder, The Different Lives of Photographic Images: How to Look at Photographs of Rape?

This paper compares two so-called “atrocity photographs” that were found in Romanian and French archives. During WWII, 18 million German soldiers traversed Europe not only with their weapons, but also with their cameras. Ten percent of Germany’s Wehrmacht soldiers owned a 35 mm camera, an instrument which allowed them to document “their” war. Most of the soldiers’ private photographs capture their everyday experiences, including violence and destruction. In rare cases, some snapshots depict rape. More precisely, they show laughing soldiers violating women’s bodies. For historians, rape photographs offer insight into the use that the depicted soldiers made of the image and the meaning of the picture in the moment it was shot. Taking the “fun”-factor and “trophy” character seriously, we can learn a great deal about Nazi military masculinities and the soldiers’ mindsets. These snapshots allow us to probe the social dimensions of sexual violence in wartime and further explore the diametrically opposed lived experiences of perpetrators and their victims. Photographs and their meaning, however, change over time. The same men most likely looked very differently at these pictures in the war’s immediate aftermath. They returned to a changing postwar German society that started to embrace a new political orientation and to adopt new frames of reference. Since 1995, amid an increasing public questioning of the Nazi past in general and the Wehrmacht’s war crimes specifically, a politically engaged, feminist reading of sexual violence has evolved rather successfully. Yet as historians of Nazi Germany now explore multiple voices and shifting meanings of photographic images, we also need to take into consideration contemporary conflicting interpretations and appropriations of such artifacts. In the wake of a so-called alternative right that is becoming increasingly self-confident and outspoken, in the United States as well as in Europe, how can we best anticipate and handle conflicting “alternative” uses of rape and atrocity photographs? This poses not only a hermeneutic but also a political challenge for scholars.

Regina Mühlhäuser, (Un)Spoken Assumptions : sexual violence during the Holocaust

Keynote

The subject of sexual practices and, in particular, sexual violence during the Holocaust has the potential to trigger misgivings and emotionally charged disputes. It involves confronting the entanglement of extreme violence with gendered sexual norms, bodily arousal, and disinhibition in a way that raises questions that are deeply unsettling to date.

The historians’ traditional methodological tool kit is inadequate when it comes to examining sexuality, and in particular sexual violence, during the Holocaust. Finding, interpreting, and representing sources poses a challenge. Researchers who work with the material have, on the one hand, to be able to read between the lines, to identify hints, gaps, and silences in the historical record. On the other hand, they must interrogate the references and meanings of generalized stories and stereotypical narratives. In both cases, they have to decode spoken and unspoken cultural assumptions about gender and sexuality.

I reflect critically on the impact of such time-dependent assumptions and ideological underpinnings that shape the experience of the historical actors as well as our approaches to this history. Taking my own work on sexual violence as point of departure, I explore what we know and what we don’t know about the entanglement of sexuality and extreme violence during the Holocaust. How can we try to grasp the experiences of victims? How can we assess the motives of the perpetrators? And in which ways can we understand the effects and symbolical meanings of this form of violence over time?